Aggressive Kindness: From Mosh Pits to Forest Roads

Weekday routines dictate that the Cruiser pulls dad duty. Some mornings, when I turn the key and the loose ground wire I still have to track down makes the speakers buzz a certain way, a memory surfaces. I feel the need to hear the songs I listened to when I started driving myself to school.

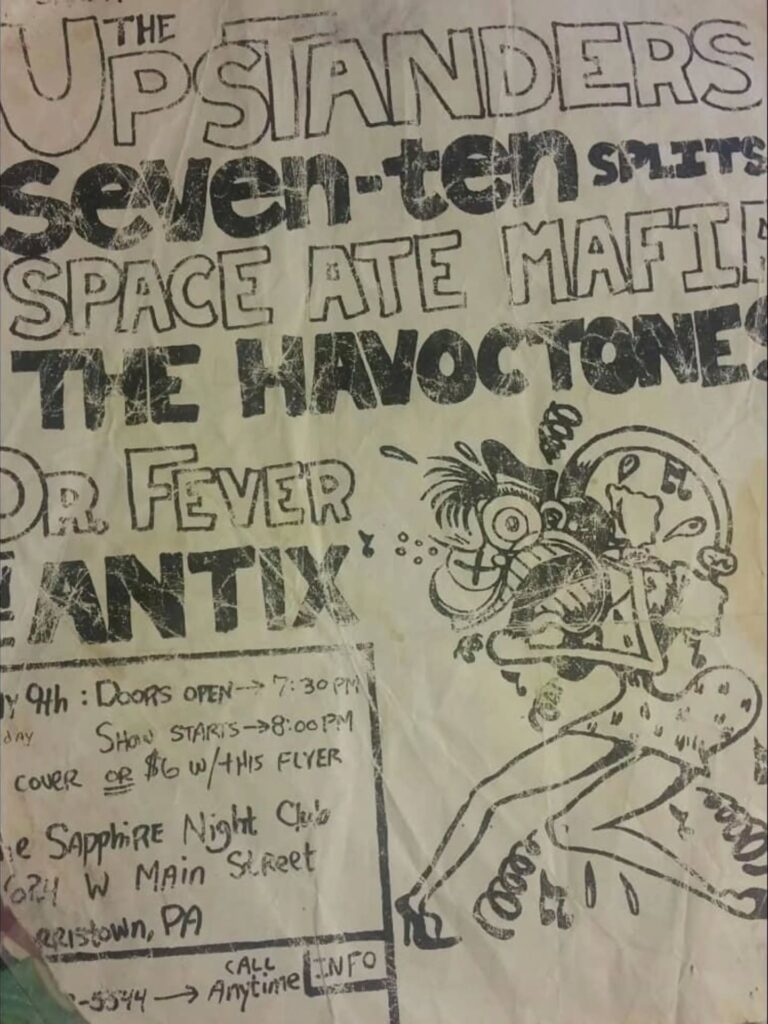

I didn’t grow up in a scene with glamorous clubs or legendary squats. I grew up with mixtapes, boomboxes, and whatever punk albums I could con out of Columbia House for a penny.

This isn’t a trail report or a stream recap.

This one’s about the soundtrack that shaped how I think about community and about the kind of person I want to be when someone around me stalls or crashes out.

I’m gonna make the subtext so loud it distorts.

What I thought punk was supposed to be

When I was a kid, the media spun punks as teens with a particular fashion sense and drug problems.

Spikes. Leather. Chains. Jackets painted with logos you don’t recognize. Somewhere in there, a safety pin through something that probably shouldn’t have metal through it.

In the grainy square of 80s MTV and letterboxed movies, a punk was the living form of directionless aggression. Their music was forks in a blender set to visuals of sledgehammers smashing the Venus de Milo.

Punk rock became the soundtrack of angry people who like to break things.

That’s not what I found.

Yeah, punk rock sounds like a connecting rod smacking your engine block at 160 beats per minute.

It was built that way on purpose: short, fast, loud. A deliberate rebellion against the overproduced stadium rock of the ‘70s.

Bands in New York and London stripped music down to the studs and played the songs like they were trying to outrun the law.

But under all that volume is something subtle and nuanced: a culture ensconced in mutual aid, individual freedom, and looking out for the people next to you, especially the ones who don’t fit anywhere else.

Nobody told me that part. I had to live it to learn it.

The first time the floor moved

I was probably about five. My sister, who is nine years older, would listen to the Ramones at top volume, morning, noon, and night.

This went on for years. It would be interspersed with other artists, but none stuck with me quite like they did.

Fast forward a few years to the first time I stepped into a real show. I half-expected a riot.

What I got instead was a living diagram of how I wish the world worked.

The music hit and the floor turned into a storm of boots and elbows. People slammed into each other, bounced off, dove back in. From the edge, it looked violent.

From the inside, it felt like organized chaos with one solid rule:

If someone goes down, you pick them up.

That isn’t just folklore.

Ask around and you’ll hear the same thing: in a healthy pit, the main rule is to look out for each other. If someone falls, you get them on their feet. If someone looks scared or hurt, you make space or help them out to the edge.

- Never leave people on the ground.

- You don’t let creeps use the chaos as cover.

- Don’t gatekeep the dance floor.

It’s rowdy, but it’s rowdy on purpose.

That was my first real lesson in aggressive kindness: you can be loud, sweaty, and furious at the world, and still treat the stranger next to you like someone worth protecting.

I didn’t have the right words for it yet, but the message landed.

Punk is for everyone. Full stop.

There’s a line I read years later that finally put words to the feeling: if there’s one core ethos to DIY punk, it’s that punk is for everybody. Anyone can sing, anyone can play, anyone can be part of it.

As an awkward kid who barely limped out of high school, that was huge. I was bored with the schoolwork; didn’t care about grades.

I didn’t think anyone thought like I did.

I definitely didn’t have a five-year plan.

But I did have a summer job that I used the money from to buy a bass guitar and a tiny amp.

It was an old Aria with a tweaked neck and a sunburst pattern. I stuck a middle finger sticker to the back and learned how to read tablature.

I’d memorize how to play my favorite songs and get to know the bands in the process.

The Bands That Raised Me

- The Ramones were proof that you could take three chords, zero subtlety, and a sense of humor and accidentally help kickstart an entire genre.

- Rancid took that energy, dragged it through working-class streets and ska basements, and wrote anthems about friends on the edge, union organizers, and cities that chew you up.

- Dropkick Murphys made working-class solidarity catchy enough to shout along with. They’ve backed unions, raised money for workers’ rights, and made a point of putting their money where their lyrics are.

- Bad Religion was the first band that made me realize punk could come with footnotes. Greg Graffin screaming about science and society on stage, then quietly holding a PhD in zoology and lecturing at UCLA and Cornell, screws with your idea of who gets to be “smart.”

- NOFX were the smartass older cousin who showed up with a skateboard, a hangover, and a stack of life lessons hidden under bad jokes. They’ve spent four decades cranking out hooky, melodic hardcore and skate punk, stayed off major labels on purpose, and still somehow became one of the most successful independent punk bands ever. Punk in Drublic turned gold while they were busy telling MTV and the big labels to get lost.

- Dead Kennedys were the band that yanked punk’s anger out of the basement and pointed it straight at mayors, presidents, and the whole polished hypocrisy machine. Surf-y riffs, razor-sharp satire, and Jello Biafra’s unhinged sermon-of-a-vocal made songs like “Holiday in Cambodia” and “California Über Alles” feel less like tracks and more like political cartoons set to 200 BPM. They were DIY to the bone, releasing records on their own Alternative Tentacles label and ending up in real-life obscenity trials and censorship battles along the way. That last point quietly taught me that “speak truth to power” isn’t a metaphor: it’s a thing that can actually get you hauled into court, and you do it anyway.

This isn’t even close to an exhaustive list. But all these bands shoved a series of lessons into my skull: being “punk” had less to do with what you wore and more to do with who you showed up for.

Punk is FOR Everyone.

No, I’m not repeating myself.

Black, white, gay, straight, bi, trans, questioning, asexual… whatever. If you were there in good faith, you belonged. If you were trying to harm or control other people, you can go find a curb to chew.

Punk rock isn’t meant to exclude anyone. It’s soft, gooey solidarity wrapped in armor. It hardens you for the realities of the world but cajoles you into still caring about the outcome and the actual human beings.

It explicitly excludes exclusivity.

What does “aggressive kindness” actually mean?

Somewhere along the way, online or in a comment thread, I ran across the phrase “aggressive kindness is very punk,” and it felt like somebody had finally named the thing I’d been feeling for years.

Another person, in a totally different corner of the internet, put it like this: being aggressively kind is way more punk than just being angry all the time.

That’s it. That’s the whole thesis.

It’s a kindness that isn’t soft.

It doesn’t mean “nice” in the way bosses use the word when they want you to shut up about your pay.

Aggressive kindness is:

- Calling out the creep in the pit.

- Making sure the kid at their first show gets pulled up, not shoved out.

- Using your voice to defend someone who’s getting piled on, even when they’re not in the room.

- Welcoming the new person at camp, on trail, or in chat like they’re already part of the crew.

It’s hospitality with teeth. Compassion with Doc Martens primed to kick down oppressive systems.

In my head, though, it’s simpler: it’s pit etiquette turned into a golden rule.

- Somebody goes down? Pick them up.

- If somebody’s getting crushed, make space.

- If someone is just trying to exist as themselves and the world is shoving back, you plant your feet and stand in the way.

Oppression is the enemy. Allowing others to live their lives doesn’t harm you.

Buddhism, back roads, and the loud part of compassion

At some point, I started reading Buddhist stuff for the same reason punk clicked: life is suffering, yeah, but what you do with that fact matters.

Compassion, or in Buddhist terms, lovingkindness, shows up there as this patient, quiet thing. Sit with your mind. Breathe. Notice. Don’t make things worse.

Punk taught me the loud version. Make things better.

Both paths are trying to answer the same question: how do you move through a broken world without becoming another sharp edge that cuts people?

There’s a saying: “East Coast people are kind but not nice. West Coast people are nice but not kind.” Growing up an hour outside Philly had its influence on my world view, too.

The second most-famous religious sect in this weird little intersection of Native America and Europe called Pennsylvania was the Quakers. Their plain speech is definitely in the mix of my personal philosophy and might be the most punk thing of all: say true things clearly and live like you mean them.

That’s what I hear in the best punk records. Strip away the distortion and it’s somebody yelling a very old idea:

“These people matter. You matter. We should treat each other like it.”

How this shows up in Adventure Adjacent

So, what does any of this have to do with my old FJ Cruiser, live streams, and forest roads?

Honestly: everything.

When I pull the FJ off pavement and creep up some rutted forest road, the same ethic applies. These places are shared. The gates and culverts and campsites exist because communities came together, planned them, and built them.

The least I can do is drive in a way that doesn’t make life harder for the next person who comes along. And if I can improve it on the way through, I do it.

Trail etiquette isn’t that different from pit etiquette:

- Stay in the lane so you don’t bruise the scenery around you.

- Don’t endanger people around you.

- If somebody’s in trouble, you stop and help.

Same story with the streams. Most days I’m just a tired guy hauling digital freight, but underneath jokes, questions, and coffee is a simple goal: build a little corner of the internet where people feel safe to be themselves.

That means:

- Moderating like a bouncer who loves the dance floor, not like a cop.

- Welcoming the quiet lurker, whether or not they say hi.

- Respecting boundaries without making it weird.

- Shutting down bigotry when it shows up, even if it’s “just a joke.”

Aggressive kindness while streaming looks like “Hey, you’re welcome here” and “Hey, knock that off” occupying the same breath.

It’s the same kind of thing I try to bring to the Field Notes.

When I write about trails, maintenance, or the quiet joy of taking the long way home, there’s always a little subtext whispering: we owe each other more care than this system wants us to give.

The punkest thing I can do at this age

Nobody would catch my old ass if I decided to dive off a stage. My mosh pit is a chat window or a comment section. My uniform is more “tired nerd with a torque wrench” than “studs and liberty spikes.”

But the bands that raised me are still just beneath the tinnitus when I’m tightening lugs on the shoulder for somebody who didn’t plan on learning how to change a tire that day.

They’re there when I’m writing another too-long blog post about some gravel road most people will never be within a hundred miles of.

They’re there when I mute a bigot in chat before they get to ruin somebody else’s night.

Punk taught me that belonging isn’t something you hoard. It’s something you hand out at the door.

So that’s the aim now:

To be the old kid in the back of the room who knows the lyrics, knows where the exits are, and is stubbornly, aggressively kind to anyone who walks in looking for a place to stand.